Despite Bill Gates’s proclamation in 1996, content is no king on the Internet. Instead, reach is king. A chapter from The Viral Inquisitor and other essays on postjournalism and media ecology. First published in City Journal.

How to sell air

Imagine you have some Nothing – pure, unalloyed Nothing – that you have decided to sell on Amazon or eBay. Imagine further that, because of some glitch, the selling platform shows your offer to 10 million users. Some people would buy that Nothing, either by mistake or out of curiosity. With a good conversion rate, you’ve got good revenue. If the glitch shows your offer of Nothing to a billion users, you’ll be a millionaire.

This scenario is no fantasy. In 2014, the funk band Vulfpeck from Ann Arbor, Michigan, posted on Spotify a new album, Sleepify, that contained ten tracks of silence. They asked fans to stream the songs on a loop, which would allow the band to collect royalties of one-half of a cent for each stream to crowdfund an upcoming free concert tour. Their fans responded enthusiastically, and the story went viral. In a month, the blank tracks were played over 5 million times, earning the band about $20,000. Spotify tolerated the gambit for a while but then took the album down.

Using this surplus value of the platform’s reach in a slightly different way, two Canadians from sunny Alberta became merchants of air. They put a Ziploc bag of air on eBay, and somebody bought it for 99 cents. They lost money on shipping but got an idea. They started compressing crisp Albertan air into cans and selling it abroad, reaching $300,000 in annual sales in 2018 through online purchases and retail stores in South Korea, where Canadian air is perhaps considered particularly sweet. They say that if they hit the retail market in China or India, sales will be in the millions. Of course, this kind of reach works even when you sell air.

These light stories suggest a heavier lesson. Despite Bill Gates’s proclamation in 1996, content is no king on the Internet. Instead, reach is king. With enough reach, one can sell anything – even air or silence.

A new form of value has emerged in the platform economy. It has little to do with exchange-value, use-value, or the concept of a commodity. A platform’s most valuable asset is connectivity: its ability to reach a sufficient number of users.

Reach is what matters: the commodity for sale is of secondary importance. Platform reach constitutes a new asset whose value exceeds the value of the underlying content. The medium is the message: for the platform as the medium, the message is reach.

The four corollaries to the network effect

So, platform reach is a new product whose value can exceed or even completely replace the value of content. How can we define this platform surplus value?

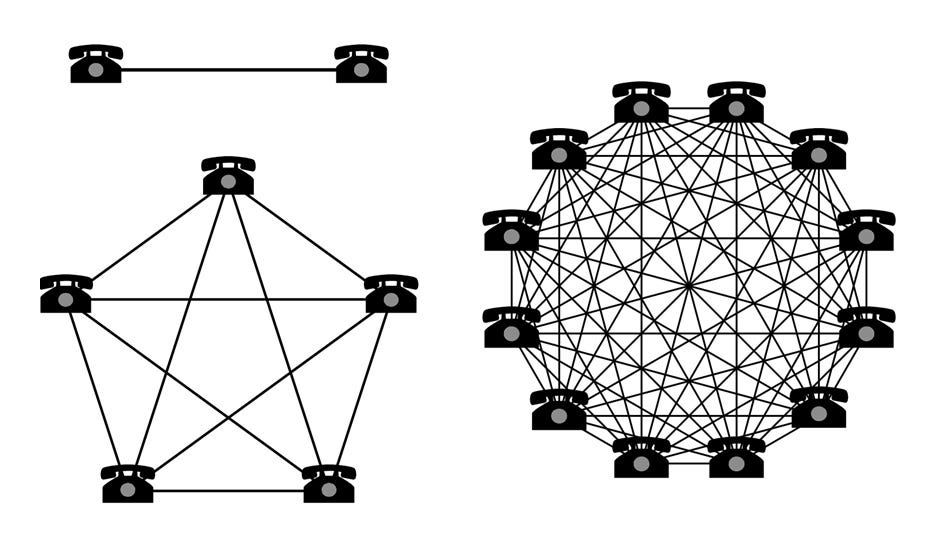

Theoretically, there is a formula for it, and it is called the “network effect.” The network effect is described by Metcalfe’s law: the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of networked users. In other words, the more users that participate, the more connections they form, and the more each of them benefits from those connections.

A good illustration of the network effect was offered by Clay Shirky in his 2010 book Cognitive Surplus. Suppose you want a ride to New Jersey at a certain time and post a request on a car-sharing service. If, after making 20 such requests, you find only a few takers, you’ll probably decide not to use the service again. The network effect was not achieved. But if you get 18 matches, the service is good. For this to happen, the service must attract all possible riders in the area. Then, you will likely find any matches you need. Somebody will drive at the needed time to the needed place.

Out of this, we can derive…

The 1st corollary to Metcalfe’s law: The best platform is a monopolistic platform.

If all the users gather on a single platform, all the possible matches between them will occur. We will benefit the most from only one Facebook, only one Google, only one Amazon, only one Twitter/X, only one Tinder, only one carsharing service. Any split (except for niche specializations, of course) will diminish the network effect and therefore the platform surplus value for us users.

This is similar to the swarming effect: the larger the swarm, the more likely individuals are to join. The viral effect works in the same manner: the bigger the viral distribution, the likelier it is that users will join and contribute to it, making it even bigger, proving its significance, and providing delivery to an even larger number of users. The network effect naturally drives platforms toward monopolization – not due to the evil will of the platform overlords (though they like it, too), but through the activity of the users if the users are pleased by the outcomes of connectivity.

The monopolization of a platform maximizes the network effects but also raises the risks associated with any monopoly, including political and policy abuses, as well as potential technical glitches – akin to the 2003 northeast power blackout caused by a software bug. Political and policy abuses, theoretically, could be overseen by regulation, but the regulation of platforms carries its own political risks, as shown by the Twitter Files.

Platform monopolization has natural limits tied to generational changes. New digital features or new generations of users arrive and undermine old monopolies. For example, MySpace was the first social media platform to reach a global audience, but then Facebook offered more advanced features and made MySpace obsolete. Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok also offered specific networking features and established a monopoly in their niches.

At the same time, all platforms seek not just niche monopoly but also universality. They consistently try to add new features to capture as many users’ activities as possible. It is conceivable, therefore, that niche platforms’ monopolies can be challenged by a super-monopoly. In this case, the universal, ultimate social media platform will eventually emerge that will embody all the possible features of social networking – from chatting and dating to video posting and digital shopping. So far, WeChat might be the closest to this universal social media platform.

The dependency of users’ benefit on the largest possible reach leads to…

The 2nd corollary to Metcalfe’s law: in the ideal network, any possible matches become inevitable.

Say you want to have a cup of coffee with someone near Times Square at 5pm and post an invite on Facebook. If you have 200 Facebook friends, the offer probably won’t be taken up. But if you have 5,000 friends and 20,000 followers, the cafeteria will not fit all those seeking to have a chat with you. In this case, people will not just statistically-accidentally coincide with you; they will want to coincide.

Robert Metcalfe introduced his law for a network of devices, such as fax machines or telephones. When the networked nodes are humans, the statistical network effect turns into a social network effect. Humans amplify connectivity by their proactive attitudes towards each other – for better or worse. They seek to coincide – to resonate with each other, especially with those capable of creating significant resonance themselves, such as celebrities and authoritative figures.

The size of one’s social graph – all a person’s connections on a platform – reflects not just numbers but also a person’s social capital. People in one’s social graph, or within one’s platform reach, are those who are interested in this person or in what interests this person. Social capital is the surplus of people who know a person over the number of people this person knows. When this surplus is significant, a person can capitalize on his or her personality in all possible ways, from professional to hobbyist, recreational, or partner-matching. This person can sell air and songs of silence.

Platforms facilitate social “capitalism” incredibly well. On top of the human-driven viral/swarming effect, algorithms calculate who might like whom or what, and then they amplify outreach by adjusting what to show to whom. Social pro-activity of interconnected users, amplified by algorithms, amplifies even more the network effect and social capital of everyone involved. These mechanisms of the network and algorithmic amplification simply did not exist when people’s social capital was accumulated offline.

Social media turn the statistical network effect into a social network effect, and this contributes to…

The 3rd corollary to Metcalfe’s law: The more benefits a network provides, the more it enslaves its users.

Three factors keep us on a given platform: its monopolistic aptitude, its habit-forming design, and the fact that users can earn a return on their investment only on the platform they’re invested in. Much like a genie enslaved to his lamp, users cannot escape these magical apps.

A positive feedback loop emerges: the more stories, thoughts, photos, shares, and memes one stores on a certain platform, the more the network effect rewards this individual. Settling in an account is akin to settling in a house and a neighbourhood. But these investments also oblige and immobilize.

This leads to…

The 4th corollary to Metcalfe’s law: the more digital belongings you have on the platform, the more difficult it is to move.

This is similar to moving in the real world: a resident of a one-bedroom apartment moves much more easily than someone who lives in a three-bedroom apartment or a house.

Here, the question of ownership of our digital belongings emerges. Who owns our social media account and everything in it? The question is easy to answer if you break your social media account down into the digital belongings it consists of. What are those belongings?

First, a personal account is a storage of posts and photos, serving as both an archive and a diary. The ownership rights to it are obvious and inalienable. This content can be comparatively easily gathered and moved. These are our digital furniture and appliances; they are bulky but still movable assets.

Another distinctive article of digital property is our connections with friends. Friends provide services: they curate and deliver news and comments, entertain, irritate, fill our lives with a sense of belonging, and sometimes lend a hand in times of trouble.

Before social media, the accumulation of friends and their services relied on family and personal (educational, professional) ties and soft skills. This was called networking long before social networks. Soft skills are no longer needed; meme proficiency is more helpful instead. Family and personal ties are mostly overrun by social media platforms. Networking is now digitized and automated.

Because of all of this, the asset of relationships is extremely hard to move to a new place. It’s not just a list of friends; it’s also their behavior, tied to the specific design of a platform. The mere list of friends does not represent the living ecosystem of relationships with its behavioral peculiarities, customs, memories, rituals, expectations, etc. The mechanical transfer of the list of friends – even if most of them agree to migrate – will not transfer the ecosystem of everyone’s friendship, because this ecosystem grew on this specific platform. On a new platform, a new behavioral ecosystem of friendship needs to be grown. One does not own his or her friends’ media habits – the platform does. A specific state of connectivity is not transportable; therefore, it factually belongs to the platform.

As always, any media service comes with a price. The platforms provide an incredible networking service; however, by extending and basically replacing our personal capacity for networking, the platforms “naturally” come into possession of the product – our networked digital lives.

Political economy of platforms

Is your content really yours after you use a platform to host and distribute it?

As soon as a user shares something on the platform, he or she also shares the property rights for as long as this person’s contribution stays on the platform and works for his or her networking. This is the price one pays for the benefit of not just reaching others but reaching them in a customized way. Exposing oneself and one’s content to both the network effect and the platform’s own business is, in a sense, a platform fee everyone pays for networking. By the very act of contributing their activities, users enter into these relationships and agree to this fee.

This relationship is symbiotic. As McLuhan once said, humans are the sex organ of the machine world – to the machines, humans are what the bees are to the plant world. Users are the bees of the platforms, indeed. They make the comb and honey for themselves, but these products – and even the bees themselves – belong to the beekeeper.

The modern criticism of platform capitalism posits that capital has become so all-permeating that it has learned to exploit even our leisure activity, such as chatting and liking on social media or watching something on YouTube. As this activity creates a product for the platforms, it should, the critique goes, be deemed “unwaged digital labor.”

Such criticism doesn’t hold up. It not only neglects the voluntary and proactive entry of users into relationships but also overlooks the fact that users receive a product, too. Moreover, the value of the product the users receive from platforms corresponds with the highest value in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – self-actualization.

The platforms capitalize on our leisure time, but they also provide a return for the investments of our leisure time in the form of growing social capital. How else would one be able to convert their leisure time into social capital? This is an incredible late-capitalist metamorphosis of surplus value.

It all results in a paradox – the platform paradox. The elements of our digital personality should belong to us, but the digital account itself – our digital persona specific to this platform – is an unalienated part of the platform.

Multiplatform multipersonality

The platform paradox can be visually illustrated if we look at our digital personas on different platforms. They are different despite being created by one and the same individual. They slightly (or not so slightly) differ in their areas of interest, manner of speech, meaning of life, and even appearance.

This transpired in a viral challenge started by Dolly Parton in 2020 when she portrayed herself as different digital personalities on different platforms: as a businesswoman on LinkedIn, a family person on Facebook, an artist on Instagram, and a playful bunny on Tinder.

Many celebrities and ordinary people participated in the viral challenge and revealed the multi-personal nature of our digital presence. We are forced to be digital multi-persons by the niche design of the platforms, as they seek to extract more of our data and attention by making us exercise the various forms of self-representation.

In the meat world, multipersonality was practiced mainly by artists and con artists. Faking an identity was normally marginalized, with the ultimate example of split personality being Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. On digital platforms, identity faking is not a bug; it is a feature. Moreover, creating better selves is a part of the platform surplus values – the truest form of Maslow’s self-actualization.

Each user is a digital multi-person who actually does not exist in an assembled form, only in its platform variations. Digital multipersonality illustrates the power of the platform design, which lures us into creating platform-specific versions of ourselves by providing platform-specific affordances. For example, Instagram favors visual bragging, Twitter favors impulsive political commenting, Facebook favors family and community connections, TikTok favors visual-motoric self-representation, and Tinder favors mating show-offs.

We plant and grow our digital clones to live our better lives, but our platform-specific personas live within the environment of a concrete platform: they are grown in, by, and for those specific conditions. Digital suicide, or deleting one’s digital presence altogether (which happened on Facebook to the Canadian media, assisted by the government), appears to be the only way to exercise one’s alleged property rights over one’s digital account. Since a platform is an environment, it technically – ecologically – owns anything grown within it.

The concept of “biopolitics” – political control over the human body – requires an update. Platforms exercise “digital biopolitics” in its ultimate form: they allow us to grow our digital bodies, and then they have them. Such is the power of platform convenience: they own us without coercion – by satisfying our essential need for socialization.

So far, the most disturbing social consequence has been the impaired freedom of digital speech. But this is just the beginning. The environmental power of the platforms over their inhabitants – our digital personalities – is limitless. Shadow banning and the cancelling of “digital bodies” on behalf of the deep state, ruling elites, or corporations, along with disabling some digital functions as a form of political punishment (such as blocking news sharing or freezing bank accounts) have already shown us the contours of the future. The next stage of “digital biopolitics” will involve social scoring: we will be obliged to deserve to live a full digital life – or pay the price.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

Profound. Illusion piled upon indoctrinated illusion. I can't even imagine how this is affecting the new generations. And I now understand better why it is hard for older generations to relate to what's happening.

where do all the posts go?

Like is there a server in ubuntustan?