Digital orality: The flip of text into texting

From "The Digital Reversal" (2025); the entire book is written in tweets—1295 of them.

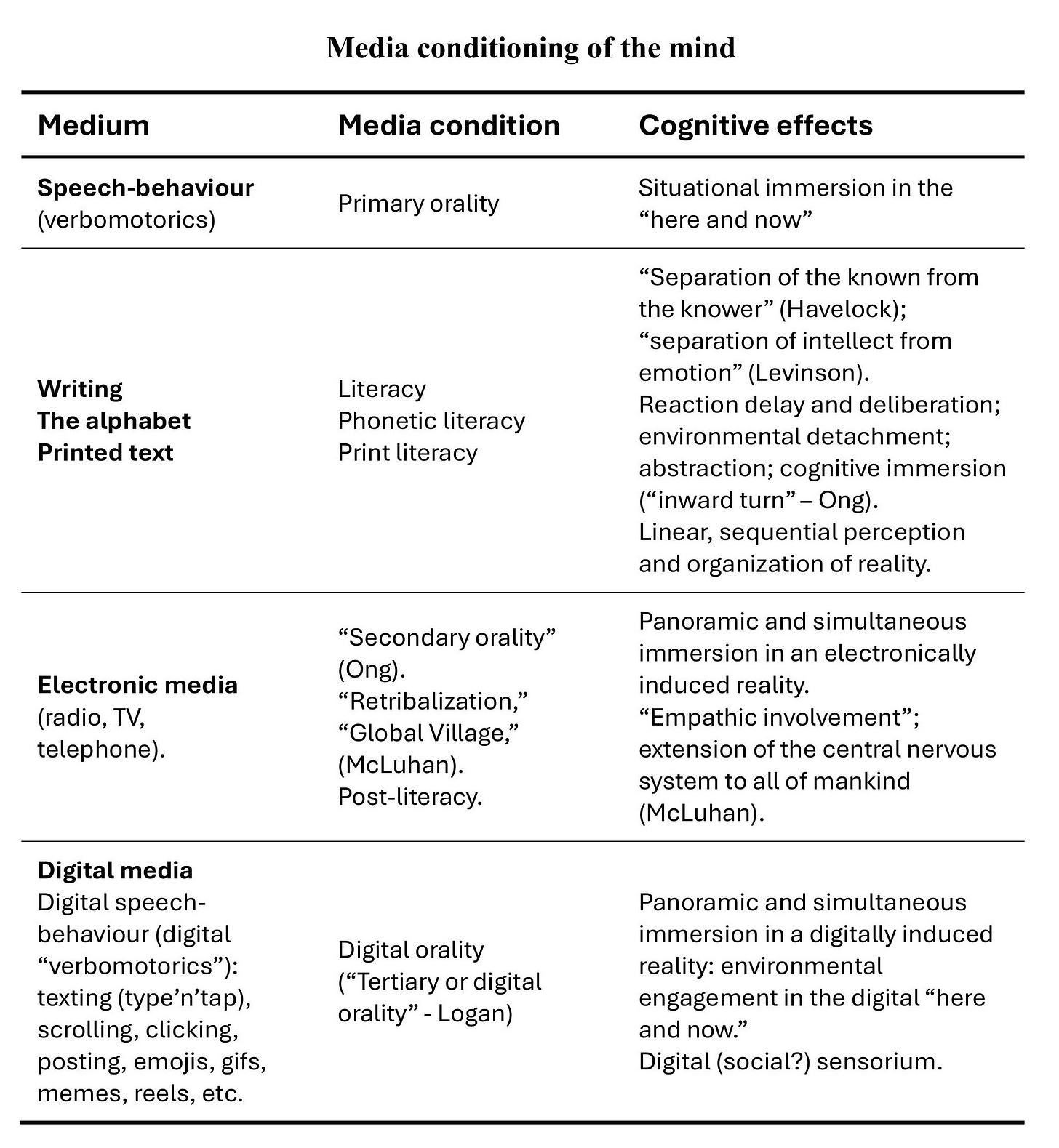

Media are the hardware of society, and culture is its software. Society follows the patterns set by media. If oral speech was the medium of orality and written speech was the medium of literacy, digital speech is the medium of a new state of mind and culture—digital orality. Excerpts from The Digital Reversal. Thread-saga of Media Evolution (just published!).

Electronic and now digital media reversed the effects of literacy, shaped over centuries by writing, the alphabet, and the printing press. This reversal of literacy and retrieval of orality culminated with the emergence of texting—digital speech, a hybrid of literacy and orality.

Digital speech blends oral and written communication. Like oral speech, it permits the instant exchange of replies; like writing, it leaves a detached record. This means people’s spontaneous reactions are no longer transient—they’re displayed beyond immediate conversation.

In physical reality, interactions are restrained by space-time limits. People can talk only in turn in a conversation or within the storytelling time—and only to those nearby. Digital talk has no such restrictions. On the newsfeed, users can talk 24/7 to the entire world.

The interactions of millions of people are accumulated, disseminated, and displayed for everyone else to react to. With the proliferation of digital speech, communication reversed from information to affirmation. We post to reaffirm our standing in the digital tribe.

By enabling rapid status gain, digital media serve the highest need in Maslow’s hierarchy—self-actualization. They create an affordance for physically and socially unlimited requests for affirmation. They even automate affirmative responses—through the button “like” and the like.

What we see as content in our newsfeed, algorithms see as stimuli for engagement. Their design does just that—boosts conversation and engagement. Algorithms amplify oral features. Social media make conversations even more engaging than organic, primary orality.

In organic orality, one cannot expose opinions to thousands, challenge revered wise men, or request affirmation across continents. Digital media enables it all, unleashing the cognitive-shaping might of orality to its full extent. Digital orality is orality on steroids.

***

The “orality” in the term “digital orality” should not be confusing—it’s not about spoken speech. McLuhan, Havelock, and Ong, when studying primary orality, were least concerned with the vocalization of phonemes. They focused on orality as a cognitive and cultural condition.

The initial interest in orality emerged in anthropology, mostly focused on folklore and illiteracy. In the 1950s–60s, the effect of TV was so profound that it led to the emergence of media studies and media ecology. Scholars began to look for patterns and analogies in the past.

Marshall McLuhan juxtaposed the effects of electronic media and print and discovered the Gutenberg Galaxy. The “comparative studies” of print and electronic media drew scholars’ attention to the cultural effects of both orality and literacy.

As Walter Ong wrote in 1982: “Our understanding of the differences between orality and literacy developed only in the electronic age, not earlier. Contrasts between electronic media and print have sensitized us to the earlier contrast between writing and orality.”

McLuhan saw orality and literacy not just as modes of communication but as contrasting types of minds and cultures. Oral people perceived the world holistically, from all around at once—like hearing (he called it “acoustic space”). Writing isolated vision and numbed other senses.

This sensory effect of writing led to the cognitive capacity to focus on the subject of writing and reading and, therefore, on the subject of contemplation. Such mental focus was not typical of the oral mind, which favored multitasking and situational, panoramic awareness.

In orality, a person is immersed in the “here-and-now” situation. In literacy, a person is detached from the environment and focused on inner vision—contemplation. As soon as the capacity for focus emerges, it diverts cognitive effort from multitasking.

Unlike the acoustic mode of perception, with its spherical and simultaneous input, the visual bias of literacy requires things to be comprehended one at a time—sequentially and linearly. Writing trains the brain not only to focus but also to structure things in a certain order.

Ordering encourages prioritizing, and prioritizing requires agency from a person comprehending the world. This is why writing enabled not just abstract thinking but also individualism—undermining tribal groupthink.

***

Writing did not end or replace orality with literacy but rather created the conditions for their complex interplay. Orality—or the residues of orality, as Walter Ong called them—continued to influence various aspects of individual and public life.

When social dynamics rely on oral exchange, people revert to orality and its regulative power. A vivid example of residual orality is the mafia. Fraternities, expeditions, debates, prisons, the Gulag, and many other groups or environments retain features of residual orality.

Orality not only survived but reemerged in a new form after electronic media enabled the transmission of spoken language. In the 1970s, Walter Ong coined the term “secondary orality” to contrast it with “primary orality”—the orality of minds and cultures untouched by writing.

According to Ong, secondary orality was brought about by “the electronic transformation of verbal expression.” This new orality was “sustained by telephone, radio, television, and other electronic devices that depend for their existence and functioning on writing and print.”

As an effect of electricity, secondary orality reflected the speech of literate societies—where minds had been trained by literacy for at least several generations. Talking on TV and radio, literate people tried to use the vocabulary and structural completeness of writing.

According to Ong, “Secondary orality is both remarkably like and remarkably unlike primary orality.” The resemblance to primary orality lay “in its participatory mystique, its fostering of a communal sense, its concentration on the present moment, and even its use of formulas.”

Like primary orality, secondary orality cultivated a strong group sense because listening (or watching TV) united people—they felt they belonged to the tribe called “audience.” Reading and writing did the opposite: they separated people by turning them inward.

However, as Ong suggested, “Secondary orality generates a sense for groups immeasurably larger than those of primary oral culture—McLuhan’s ‘global village’.” The oral tribe was limited by physical reach; the electronic affordance to overcome space-time removed those limits.

Ong noted that, before writing, oral individuals were group-minded by default—they had no other way to see themselves. “In our age of secondary orality, we are group-minded self-consciously and programmatically. The individual feels that he or she... must be socially sensitive.”

The synchronized electronic engagement with others promoted the display of spontaneity. But this spontaneity was performative. Fake it till you make it: following TV role models, people often simulated spontaneity to display openness and “empathic involvement.”

As Ong sarcastically concluded in this regard, “We plan our happenings carefully to be sure that they are thoroughly spontaneous.” According to him, secondary orality was “essentially a more deliberate and self-conscious orality.”

By enabling distant involvement, electronic media not only created the tribal unity of audiences but also ensured the absence of physical togetherness. The audience is never present—only assumed (or simulated in a studio). “The audience is absent, invisible, inaudible,” said Ong.

***

Just as TV did in the time of McLuhan and Postman, digital media turned the attention of media ecologists to past media eras in search of patterns and analogies. The speech of chats and newsfeeds wasn’t like writing and didn’t represent secondary orality. It was something new.

Ong’s concept of secondary orality inspired Robert Logan, a physics professor at the University of Toronto and co-author with Marshall McLuhan, who in 2007 coined the term “tertiary orality,” which he also referred to as “digital orality.”

Logan described “tertiary or digital orality” as “the orality of emails, blog posts, listservs, instant messages (IM) and SMS, which are mediated paradoxically by written text transmitted by the Internet.”

Logan used the term before smartphones and social media, so at the time, he couldn’t observe in detail the hybridization of oral and written speech into digital speech that occurred when texting became the dominant mode of digital communication.

Logan’s derivation of “tertiary or digital orality” from Ong’s idea was a genuine insight—a farsighted introduction of a definition whose meaning continues to unfold as the ongoing development of digital media reveals new features of the phenomenon.

***

What defines orality as a cognitive and cultural trait is not vocal performance, but its opposition to literacy, which forms the dichotomy “environmental/tribal immersion vs. detachment.” Similar to the condition of primary orality, digital media enable environmental immersion.

Digital orality began with forums and chats and exploded with social media. It spread to all activities requiring digital interaction, now involving not only speech but also all actions mediated by click, tap, or typing—thus shaping a person’s entire digital behavior.

The behavioral nature of any digital action is what makes it immersive and therefore opposite to the cognitive conditions of literacy. Texting is organically embedded in digital behavior, just as oral speech was embedded in situational behavior in physical reality.

Before writing, people could hardly isolate words. There were no words—only names of things or actions; names belonged to situations, not to utterances. According to Walter Ong, oral interaction was “performance-oriented rather than information-oriented.”[x]

Ong borrowed the French word verbomoteur to describe it. Oral talk is a muscular activity—meaning is conveyed not just by words but also by nonverbal cues sent by the body. In a sense, language did not exist before writing, and even speech was, in fact, speech-behavior.

Writing—especially phonetic writing—cut off words from objects and actions and turned them into abstractions detached from situational needs. With this semantic detachment, the mind itself withdrew from the “here and now” and opened up to abstract thinking and contemplation.

Handwriting preserved some residue of personal “verbomotorics,” like individual inscriptional traits, but printing fully disembodied text. Beyond literary style, printed text bore no personal mark. It was its uniformity that enabled the civilizational breakaway of print cultures.

The typewriter retrieved the individual body’s contribution—now to the production of uniform text: individual typing emerged. Now, digital typing has fully restored personal touch in the very technology of text production. Digitally modified—and emancipated—text begat texting.

Texting retrieves speech-behavior, but in digital form. Emojis mimic gestures and facial expressions. Abbreviations like LOL or OMG work as digital exclamations. CAPS LOCK YELLS. Memes and GIFs complement digital speech-behavior, as proverbs and sayings did in oral culture.

***

Just like oral speech, texting is (1) conversational and (2) behavioral. It immerses the user in a “here-and-now” situation, but this situation is digitally induced. That’s only logical: the discarnate user enters digital reality through digitally (dis)embodied speech-behavior.

Media evolution persistently pushes us to behave digitally in the most convenient—and addictive—ways. Digital means of interaction, from keyboard to touchscreen, grant users a wide variety of ways to express speech-behavior.

Texting has already evolved into typing’n’tapping: virtual keyboards offer Pinyin-like input for alphabetic languages. You start typing, and the keyboard suggests a word or a picture. It’s possible to compose an entire phrase from pictograms—just as the early Sumerians did.

This affordance erodes the cognitive skill of alphabetic speech construction, reversing abstract words into names of objects and actions, inseparable from them. It’s a handy solution for fast situational interaction—too bad abstract thinking has no room in it.

In addition to typing’n’tapping, new media offer new means of “digital verbomotorics”: clicking, posting, scrolling, web-surfing, liking, screenshotting, friending, banning, muting, uploading, tagging, sharing, subscribing, streaming, tweeting, skyping, tiktoking, and more.

Under the pressure of these affordances, cognitive habits nurtured by print literacy reverse from environmental detachment to environmental immersion. Digital speech-behavior is just as immersive as its oral kind, but within a different, induced environment.

(Curiously, digital utterance consists of texting and posting—distinct actions, technically allowing for delay. Yet digital speech-behavior remains highly impulsive. The temptation to click seems to affect the brain more strongly than the illusory affordance to delay posting.)

Digital interactions may still be speech-centered when texting is involved, but not necessarily. Digital speech-behavior is becoming less about speech and more about behavior—which is totally natural in environmental immersion but ill-suited to detached contemplation.

***

In the 1960s, Marshall McLuhan noticed that electronic media immersed the human mind in a simultaneous, panoramic perception of reality, similar to oral perception. He argued that this media effect led to “retribalization” and transformed civilization into the “Global Village.”

But TV only allowed people to feel immersed as viewers (what McLuhan called “empathic involvement”). Unlike TV, digital media gave people the power to speak and act, turning the passive emotional involvement of the TV era into active, participatory engagement.

In the big picture, electronic media reversed the rational detachment of print literacy into the emotional involvement of TV, but digital media reversed the emotional involvement of TV into the impulsive engagement of social media.

***

Why do social media retribalize society? Because, to commodify engagement, they encourage users to display their impulsive reactions to each other. This retrieves the tribal condition of humans’ mutual impulsive exposure, atypical for literacy but typical of orality.

Users’ impulsive engagement sustains the business of platforms and supports the entire ecosystem. More engagement makes more commodity—and more tribalism. It brings users the benefits of accelerated socialization—but also retribalizes society on a global scale.

This effect of social media extends to all digital media—to any medium where interaction is mediated by clicking and therefore fosters impulsive reactions. Though to a lesser degree, all digital interfaces retrieve the impulsive behavior of orality simply by being interactive.

Books couldn’t do that.

***

When digital media reversed cognitive detachment into situational immersion, it set off other reversals. The structured, fixed world built by literacy reversed into a “natural” flow: the newsfeed pouring into our devices. The flow has no structure or completeness, typical of literacy.

As soon as structuring, selection, and completeness are reversed, digital orality dismantles other logical structures brought about by literacy. Without structuring, content returns to the natural—tribal—forms: storytelling, social grooming, and quarrel.

Impulsive reactions replace deliberation. Situationally tied personal anecdotes replace abstract consideration. Literacy is substance-oriented, and orality is relation-oriented; the reversal from the former to the latter retrieves tribal relations built on empathy and agonism.

By reversing information into affirmation, digital orality retrieves not only relational bias and agonistic intensity but also other traits of primary orality: bragging, truth relativity, analog thinking, and magical consciousness (fueling the rise of science denialism).

Even those avoiding social media are impacted by their effects. As McLuhan once said, if you don’t have a TV, you miss all the fun it provides but still suffer the consequences it brings. Digital orality shapes social conditions for everyone, whether they’re online or not.

Social media emerged in the mid-2000s, and the full demographic transition to digital platforms was completed by 2020. These 15 years—an extended decade—marked a cognitive and cultural pivot comparable to the Axial Age, but in reverse.

See also books by Andrey Mir: