In the early 2010s, old institutions transitioned to Web 2.0 and adopted the values of early digital users—young, urban, educated, progressive. The news media, desperately hoping for digital prospects after losing traditional revenues, were the first and the most affected by this demographic and value shift among traditional institutions. This is where today’s political divide and polarization began. Excerpts from The Viral Inquisitor and other essays on postjournalism and media ecology.

The first users of new media always dictate their values to the rest of society. Until…

The Digital Rush was a cultural movement of the early 2010s, when traditional institutions rushed to adopt digital technologies and, therefore, digital culture. They targeted the leading digital demographics at the time, the digital progressives, and embraced their ethos along the way.

The process itself is not unique: any medium empowers its early adopters and imposes their values on the rest of society. A new culture always rides the wave of new technologies. In the Bronze Age, those possessing the technology of ironware wielded dominance over all others. Similarly, those who first harnessed the discourse-formation power of digital media gained an opportunity for cultural dominance even when lacking other, more traditional advantages.

This time, however, due to the instant proliferation of the new dominant medium, it took just a decade, not centuries, and the aging of the early new-media adopters could not mitigate their disruptive and oftentimes nihilistic aptitude typical of the youth, normally marginal to the establishment.

The young and progressive digital visionaries of Silicon Valley provided the hardware for societal changes, while the young and progressive discursive elites, among the first to digitize, introduced their cultural software into all societal practices—from politics and education to pop culture, journalism, and corporate standards. Technology always comes with an ideology; this is how it happened this time. Society has submitted to the new values, propelling their source, the digital progressives, from activist marginalia to the establishment.

As a result, the entire corporate culture was influenced by the cultural values, previously marginal, of those demographic strata who had digitized first. Just as the first European settlers of America imparted their religious and moral design to the entire American culture for centuries to come, the first digital settlers defined the design of digital society and laid the foundation of corporate culture in the digital era. Capitalism adapted once again in its history, this time by absorbing activist cultural agendas into its profit-making mechanisms.

Such was the immediate effect of the Digital Rush of the early 2010s.

Soon, however, reactionary backlash and nostalgic ressentiment fired back. Excluded from the mainstream agenda, the older, less urban, less educated, and less progressive demographics reached the critical mass of social media use sometime by the mid-2010s. Much like their younger and more progressive predecessors 5–7 years before, they became able to communicate to each other their indignation regarding the establishment, now captured by progressive ideas. This indignation, triggered by the mainstream media and amplified by social media, turned into a political demand and led to Brexit, Trump, and all the subsequent waves of right-wing reactions. The conservative backlash of the late 2010s was the secondary, recoil effect of the Digital Rush of the early 2010s.

The sum result was soaring polarization. Political and cultural struggles have moved onto the new media hardware and embraced its settings. Since the main effect of digital media, particularly social media platforms, has been to catalyze self-expression, the cultural, political, and economic significance of identity claims has skyrocketed. <…>

Read further in The Viral Inquisitor and other essays on postjournalism and media ecology

The Digital Rush in the news media: the mutation of journalism into postjournalism

Throughout the twentieth century, journalism was funded predominantly by advertising. But in the early 2010s, after losing ad business and having no support from print subscriptions, news orgs turned to their last hope—digital subscriptions. They started wooing the digital audience.

But who was the digital audience at the time, in the early 2010s? The proliferation of social media began with the young, urban, educated, and therefore progressive. To sell digital subscriptions, the media needed to find ways to attract this digital audience (as there was simply no other digital audience at the time).

This is not to say that journalists were complete strangers to the digital public. On the contrary: journalists usually come from the ranks of urban, educated, and progressive elites. Many of them were themselves social-media pioneers. Journalists, therefore, were naturally predisposed to align with the dominant ethos of early social media – in part, because they “have always been more liberal than their fellow countrymen,” as Batya Ungar-Sargon pointed out in her 2021 book Bad News. “But in the past,” she maintained, “this liberalism was checked by their publishers, who were often the owners of large corporations, or Republicans, or both. They wanted their newspapers and their news stations to appeal to the vast American middle, which meant that journalists were not at liberty to indulge their own political preferences in their reporting.” [1]

Indeed, the ad-based business model had kept the natural liberal predisposition of journalists in check. The balance between the liberalism of the newsrooms and the business necessity to appeal to the “vast middle” for better advertising maintained both the market value and cultural power of journalism.

Yet the essential ingredient of that recipe – the advertising-dictated necessity to appeal to the median American—had disappeared by the early 2010s. The inherent liberal predisposition of newsrooms was suddenly unchecked by any financial imperative. Now the news media needed to appeal to the digital progressives.

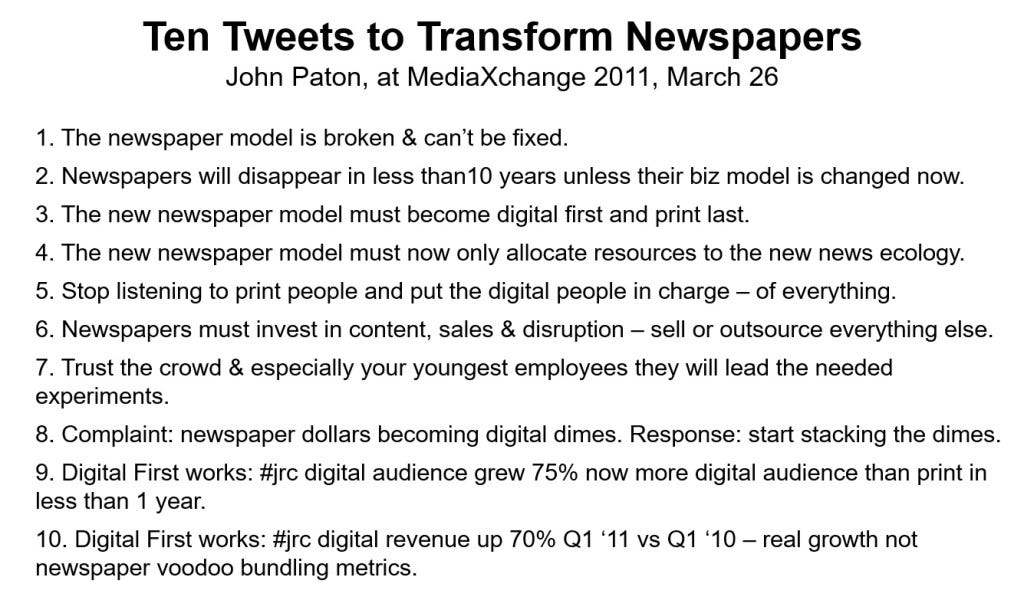

In his famous 2011 theses, “Ten tweets to transform newspapers,” publisher John Paton (who issued the call “Digital First!” for the industry) stated: “…Trust the crowd & especially your youngest employees: they will lead the needed experiments.”[2] And so the media naturally did: they submitted to the digital crowd and younger demographics; the digital crowd happened to be the younger demographic, eager for societal changes.

“Ten Tweets to Transform Newspapers” – Digital First! manifesto by John Paton, 2011. Digital First! seemed to bring incredible growth in the beginning, as this was growth from a very low base. Bottom line: Digital First! affected policies but did not save the business.

As a result, the principles of news coverage changed dramatically. Coverage became determined not by the necessity to reach out to the “vast middle” but by focusing on pressing social issues highlighted by the progressive Twitterati. Quantitative studies indicate that the use of terminology associated with woke politics, such as “racism,” “people of color,” “slavery,” “white supremacy,” and “oppression,” has skyrocketed in the American mainstream media precisely since the early 2010s.[3] This radical shift affected the entire news ecosystem. TV and radio needed to “go digital”, too. They started developing their own digital addictions and dependence on social media crowds.

Frequency of prejudice-denoting words in written news media

The frequency of prejudice-denoting terms in the New York Times and the Washington Post news and opinion articles, by Rozado et al. [4] In total, the study analyzed word use in 27 million news and opinion articles written between 1970 and 2019 and published in 47 of the most popular news media outlets in the United States and detected similar patterns. The study registered the statistical change in language and the synchronization between the media but did not make any connection to the political economy of the media. The surge, however, clearly correlated with the Digital Rush – the switch of the news media from plentiful ad revenue to desperately seeking digital subscriptions in the early 2010s, when the digital audience had very specific social-demographic characteristics: mostly white, urban, educated, and progressive youths.

This happened historically instantly between 2010 and 2016. In terms of social effect, the loss of advertising and focus on the digital audience resulted in a shift of the media from representing a broader populace to representing its digitized and most progressive part. <…>

Read further in The Viral Inquisitor and other essays on postjournalism and media ecology:

- The Twitter revolution continued: from Occupy Wall Street to MAGA

- Mutation into postjournalism completed

See also books by Andrey Mir:

[1] Ungar-Sargon, Batya. (2021). Bad News: How Woke Media Is Undermining Democracy. Encounter Books. P. 7.

[2] Paton, John. 2011, March 26. Ten tweets to transform newspapers. IndieWire.

[3] Ibid. P. 4.

[4] Rozado, David, Al-Gharbi, Musa, and Halberstadt, Jamin. (2023). Prevalence of prejudice-denoting words in news media discourse: A chronological analysis. Social Science Computer Review, Vol. 41(1), pp. 99–122.

Thanks so much for putting this together in a comprehensible form. Our societal polarization is a bit of a philosophical obsession of mine. I continue to critique it primarily through our historically philosophical structures of remembering. All the foundation myths of what I call the three C’s: Christianity: Colonialism: Capitalism possess a structural dualistic monotheism which expresses through constant social conflicts which are justified by ideologues of the Times. Catholic v Protestant: Ancients v Moderns: Right v Left etc… This paradigm always seemed to me to be lazy and indulgent.