The encyclopedia of the Toronto School of Communication

Toronto has definitely been not just a "meeting place," but also a place of force. A review of "Wisdom Weavers."

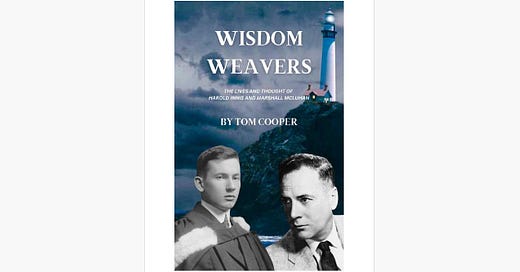

A review of Wisdom Weavers: The Lives and Thought of Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan by Tom Cooper (2025, Connected Editions*, with Preface by T. C. McLuhan and Foreword by Robert Logan; presale available on Amazon).

Tom Cooper’s Wisdom Weavers: The Lives and Thought of Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan has a near-cinematographic dramaturgy. Two storylines develop independently but on a “collision course,” ultimately bringing two of Canada’s most influential intellectuals together in the city of Toronto, whose name, in a local Indigenous language, means “meeting place.” The author narrates their stories as the unfolding of fate. Step by step, in the context of the great technological breakthroughs of the early 20th century, the dual story reveals how Innis’s and McLuhan’s intellectual formations predestined their “collision.”

The reader can observe how Innis’s connection to farming formed his ecological thinking and his understanding of the impact of technological innovations. McLuhan’s mother, Elsie, a performer and elocutionist, influenced his style as a reasoner, whose writing was metaphorical because his thinking was sharp-tongued. Cooper diligently selects this and other details from the social and personal contexts that shaped Innis and McLuhan. The tension grows, the storylines converge, and culminate in… a collision indeed, as their first meeting ended in an irreconcilable religious debate. The dramaturgy of their journeys—of becoming and moving toward each other, or rather toward a unique ecological understanding of communications—is captivating and could have served as the plot for a dual-biopic screenplay.

This, however, makes hardly half of the book. The other half scrutinizes their influence on each other (mostly that of the older Innis on the younger McLuhan, of course) and on the entire world. Harold Innis was the towering figure in the political economy of his time, but fellow economists were rather puzzled by his switch to studying communications, which was not even an established discipline at the time. With all his prominence in economics, Innis would likely have just secured a spot in the history of economic theory by now, if not for McLuhan. Inspired by Innis and expanding on his idea of media effects, McLuhan carried Innis’s torch in communication studies, reserving for him a place as a founder of the field and a forerunner of media ecology, which now constitutes the greatest part of Innis’s legacy. Without McLuhan’s extension, Innis might have remained a name in the history of political economy; with it, he became highly relevant as a communication scholar. His ideas on media bias and their effects on empires and civilizations remain—and will continue to remain—relevant and productive. I am not sure if Tom Copper agrees with such an interpretation of the Innis-McLuhan “collision,” but that’s how a reader’s perspective looks after reading their paralleled biographies.

Cooper’s book explores how the dynamic between the two “tall Canadians” started, developed, and transferred into the future – our present and beyond. The analysis is based on witty biographical storytelling, a comparative analysis of ideas and their transformations. Some of Cooper’s findings might sound like speculations but are remarkable in their insight. The one I found most amazing illustrates an imaginary transformation, constructed by Cooper, of Innis’s observation into McLuhan’s most famous one-liner, “The medium is the message.” The passage deserves the full quote:

For example, consider this published excerpt from Innis’s writing. (I have 1. italicized words which distinguish Innis’s style and perspective from McLuhan's and 2. bolded remaining words, which, when considered alone, resemble McLuhan’s more laconic telegraphy.)

Innis: We can perhaps assume that the use of a medium of communication over a long period will to some extent determine the character of knowledge communicated and suggest that its pervasive influence will eventually create a civilization in which life and flexibility will become exceedingly difficult to maintain and that the advantages of a new medium will become such as to lead to the emergence of a new civilization.

With Innis’s carefully italicized qualifications eliminated, his bolded quotation would read “A medium of communication will determine knowledge...and a new medium will lead to a new civilization.” A further reduction of this theme would state: “A medium...will determine...knowledge,” and declare: “A medium will create a civilization.” From this compression, it is a small leap to declare the bold proclamation that “the medium is the message.”

In another innovative device, Cooper analyzes writings on Innis and McLuhan through the lens of dramaturgy, as if specific media play characters (“King Clay,” “Queen Printing Press”) in an historical drama, or rather saga, of media evolution. This original approach indeed gives a holistic view of media development as represented in the works of Innis and McLuhan.

This interplay of thoughts and styles is central to Cooper’s dual analysis of “two greyhounds,” as he often called Innis and McLuhan at the instigation of Tom Easterbrook. A younger colleague of Innis and a close friend of McLuhan, Easterbrook introduced the latter to the former and chaperoned their first meeting. Being shorter than the two, he felt like a “poodle” sandwiched between “greyhounds” when the trio walked down the campus. As we can see, the book, while heavily focusing on academic and intellectual matters, is not a pedantic volume (though factual details and names are presented with plenty of pedantry), but also a vivid story with colourful metaphors and allusions. As a true McLuhanist, Cooper does not skip producing his own coinages and neologisms, such as “McInnis” or “presearch” (a preventive search for the effects of newly introduced media before their effects on society become evident).

Innis and McLuhan did not work together, except for a brief period during interdisciplinary seminars known as the “Values group” in 1949. Shortly after, McLuhan wrote to Innis about the “possibility of establishing an entire school of studies” based on Empire and Communications. Innis expressed interest and asked to keep him updated. Unfortunately, Innis passed away soon afterward, and no organized study group uniting the two ever came to fruition.

However, the term “Toronto School” appeared—much later—primarily as a metaphor to capture “the diffusion of ideas and influence here, networks of interaction and relationships,” as Lance Strate described it in an interview. [1] In a special section titled “Was There a Toronto School?” Cooper outlines how the idea of the Toronto School emerged to bring together the various activities and scholars exploring communication and culture in Toronto. Perhaps this activity was not sufficient to formally recognize the Toronto School in the same way as the Chicago or Frankfurt schools. Nonetheless, over different periods, with various inspirers and organizers, Toronto saw the rise of proto-forms that could have solidified the concept of the Toronto School at a formal level. Among the events and endeavours that could have become progenitors of a school of study were:

Innis’s “Values Group” in 1949, with early McLuhan among the debaters,

McLuhan and Carpenter’s journal Explorations in the 1950s,

the McLuhan-led Centre for Culture and Technology, later the McLuhan Program in Culture and Technology (since 1963),

the famous McLuhan’s Monday night seminars in the Coach House (the 1960s-70s), restored for several years in the 1990s through the 2010s,

Paolo Granata’s Toronto School initiative with the memorable international 2016 conference “The Toronto School: Then, Now, Next,”

Andrew McLuhan’s “Understanding Media” seminars and the McLuhan Institute near Toronto (since 2017),

Robert Logan et al.’s journal New Explorations (since 2020).

…And other undertakings – I’ve surely missed something. Even though they weren’t united by a single structure or continuity, they represented an astonishing geographical concentration of pursuits in communication study. So, Toronto has definitely been not just a “meeting place,” but also a place of force.

Having introduced the Toronto School with a question mark, Cooper subsequently uses this title to describe this virtual college of scholars—and justly so. The book covers arguably all the key concepts and also quotes or mentions everyone involved in the Innis-McLuhan binary-star orbit, including those carrying their legacy. This is what constitutes the Toronto School, both historically and in the present. With such scope and depth, Wisdom Weavers: The Lives and Thought of Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan is truly the encyclopedia of the Toronto School of Communication.

To add a hint of criticism to the review, there are two aspects of Wisdom Weavers that caught my eye. First, there is some redundancy in the technological context when describing the childhoods of Innis and McLuhan. The idea is clear—to show how life itself, or rather the evolution of media and technologies, craved someone to come and describe what was happening. The author seems to have collected nearly every technological innovation, great and small, to connect them with the timeline of the two protagonists’ emergence and development. However, at times, it becomes a bit too much and distracting. Moreover, readers of such literature are likely already familiar with the technological context of the era, so they can grasp the idea with fewer prompts.

The second issue is not so much an issue but rather a missed opportunity to broaden the book’s audience. After contemplating the biographies of Innis and McLuhan and their eventual collision course, Cooper delves into a parallel analysis of their theories, starting with the debate on determinism. While jumping into such a discussion is entirely appropriate for readers with some background in communication studies, it may prove challenging for those without prior expertise. A brief introduction to key concepts, such as media ecology and determinism, could have widened the audience, making the story of the two “tall Canadians” more accessible to the general public. This approach, for example, was effectively employed by Lance Strate in his 2017 Media Ecology. After providing historical and methodological context, he organized his analysis around four fundamental concepts—“Medium,” “Bias,” “Effect,” and “Environment”—structuring chapters around each.

Curiously, Tom Cooper later employs a somewhat similar approach, albeit with a different logical framework. Instead of emphasizing a hierarchical arrangement of concepts, he structures the content around intellectual biographies, transitioning from the lives of Innis and McLuhan to their legacies, addressing specific concepts as they become relevant or emerge throughout the narrative. This structure sometimes highlights central concepts, such as the Laws of Media, while at other times it singles out less prominent ideas into subsections.

Such structure, however, has its merits: chapters are divided into short thematic segments with subtitles that provide rhythm and flow to the reading. The book is written with academic rigor but in a vivid and engaging style, making it quick and pleasant to read despite its substantial length. It encompasses everything related to the two most famous Canadian scholars, from their lives and relationships to all relevant events, key concepts, and the people involved in their orbit—both then and now. It also covers books devoted to them or applying their ideas in various fields, as well as related websites, plays, and even board games, making Wisdom Weavers truly an encyclopedia of all things Innis and McLuhan.

* Connected Editions was the publishing arm of Connected Education, created and administered by Paul Levinson and Tina Vozick, which offered online courses for academic credit granted by the New School and other universities in the 1980s and 90s. Levinson decided to continue Connected Editions as a small press with a focus on media studies and on science fiction. Levinson worked with Marshall McLuhan, organized a Tetrad Conference with McLuhan in 1978, and has published numerous articles and several books about McLuhan, including Digital McLuhan (1999) and McLuhan in Age of Social Media (2015-2024).

**See also my review of Paul Levinson’s sci-fi novel The Plot to Save Socrates (2006): “Time travel and media ecology.”

[1] Ralon, Laureano. (2010, August 18). Figure/Ground Interview with Lance Strate. Lance Strate’s blog Time Passing.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

The Viral Inquisitor and other essays on postjournalism and media ecology (2024)

Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)