The features of orality: Bragging

Orality has no appetite for objectivity—and neither does digital orality.

Bragging is a source of accumulating personal stories into the tribal encyclopedia. Before literacy—and after it—bragging transformed significant events into significant stories, thus enabling cultural records that legitimized tribal hierarchy. A chapter from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

Robert Logan observes that the Hebrews were the first people who created a nonmythological and realistic history of themselves. The other literate cultures of the ancient world, from the Sumerians and the Egyptians to the Assyrians and the Hittites, recorded their historical events, but their historiography was crude, events were recorded in isolation, and, most importantly, they tended to record mostly their glorious moments.

According to Logan, it was alphabetic literacy that helped the Hebrews develop a historic sense. “The Hebrews connected the events and imbued them with purpose. They also had a measure of objectivity, recording both the events of which they were proud and those of which they were ashamed,” writes Logan.[1] He also notes, implying the influence of the alphabet, that the Greeks developed a similar objective method of historiography.

Orality has no appetite for objectivity. On the contrary, all the functional features of orality – collective involvement, status competition, the request for affirmation, and environmental immersion with its imperative of occupying more or new space for greater benefits – emphasize the affordance and necessity of bragging. By its very psychological nature, bragging repels sober self-reflection that could be detrimental to tribal authenticity.

Bragging might not be encouraged in a literate society, but in orality bragging is a beneficial strategy or even a survival strategy. In an oral culture, everyone is exposed to the collective. Evolutionary selection developed these personal exhibitions into requests for recognition and appreciation. Everyone seeks to be exposed in a way that provides better “social security” – greater benefits from others. Such subliminal requests for affirmation simply have to project the importance of the speaker. Any speech act is inherently also a show-off.

Bragging, however, can involve not only tales of victorious deeds or significant events but also tales of great suffering, which grew in importance as social development led to the growth of empathy. Empathy provides benefits for the weak, and since weakness became a peculiar form of social capital, it needed to be shown off properly.

Through bragging, people contributed their victorious stories and the stories of great events to the collective body of individual tales. These tales also held instructive potential regarding acceptable behaviour and survival strategies. When hunters brag about a good kill, warriors brag about a victorious battle, or farmers brag about a good or bad year, they collectively supply and renew the standards of successful behaviour. Bragging is a collectively and mutually taught school of success and survival.

Another cumulative effect of individual bragging relates not just to maintaining behavioural standards but also to the accumulation of knowledge. Bragging stories were selected in accordance with their significance and, if worthwhile, reiterated or recited by others. If, at the individual level, bragging was a request for acceptance and appreciation, at the collective level, the multiplicity of individual bragging worked as a recording device within a family or a community. Bragging served the historization of personal and tribal events. The worthwhile individual, family, and tribal show-offs were poured into collective operative memory and fermented there. This collective processing of individual bragging defined and refined the significance of events for recording in the collective device of oral memory.

As Stuart Hall noticed regarding a similar function of television, “The event must become a 'story' before it can become a communicative event.”[2] Bragging transformed significant events into significant stories and thus enabled cultural records that legitimized tribal hierarchy, conducted tribal indoctrination, and passed on tribal instructions containing outstanding experience. At the roots of any heroic epic lies banquet bragging. Bragging is the foundation of the “tribal encyclopedia,” a term Eric Havelock coined to describe Homer’s poems. If skilled individual show-offs amplified personal social capital, then proficiency in bragging on behalf of the community created the professions of bards as well as politics and diplomacy.

Until today, many stories shared among people can easily be interpreted as bragging about one’s remarkable experiences. Bragging appears in casual conversations at friends’ gatherings, in family anecdotes shared at the dinner table, in small talk at social events, or in presentations at business conferences. The exchange of bragging serves the same role as the phatic function: it establishes and maintains mutual relations for the speaker’s benefit, but with special focus on the speaker’s importance.

Since orality is relation-oriented and literacy is object-oriented, literacy mitigated the psychological intensity of bragging and “afforded” the emergence of modesty. The ultimate assault of literacy on bragging is represented in the juridical form of the non-disclosure agreement. The non-disclosure agreement is the ultimate killer of orality.

Digital orality has reversed that and retrieved bragging. It is not without reason that the design of social media platforms, whether Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, or TikTok, exploits and encourages different forms of bragging. This ranges from pictures of food and travel, geo-tagging check-ins, and name-dropping to listing personal titles in profiles, demonstrating meme proficiency, and posting intellectual exercises. What else are our posts and profiles if not requests for appreciation, or bragging, from its very primitive to very sophisticated forms?

(An excerpt from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.)

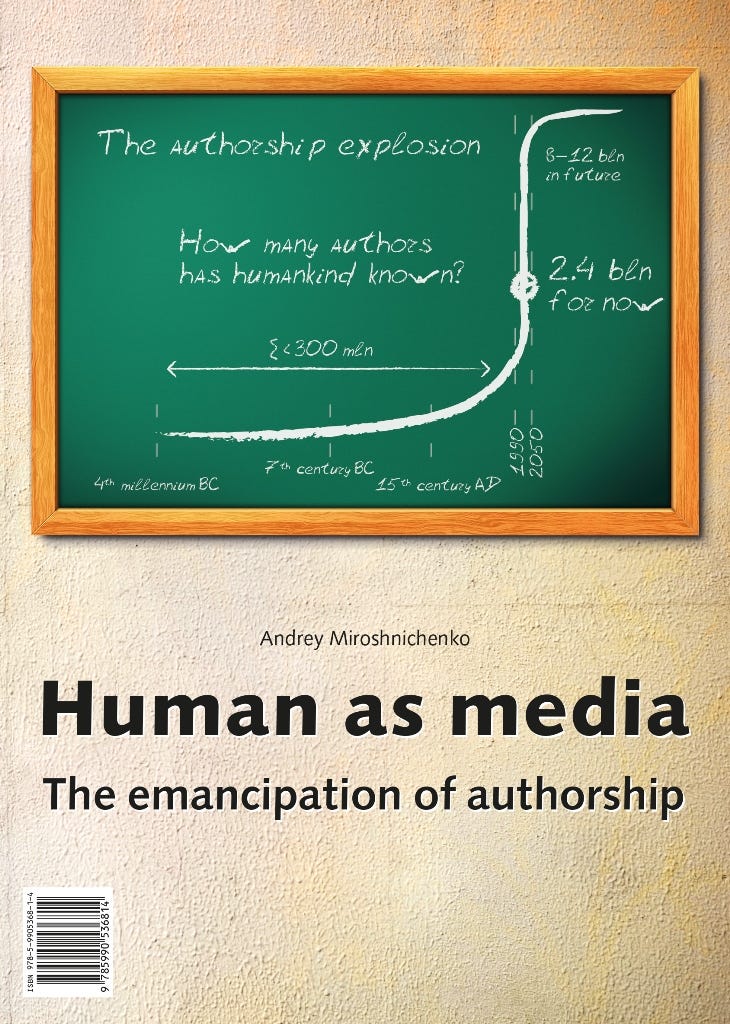

See also books by Andrey Mir:

The Viral Inquisitor and other essays on postjournalism and media ecology (2024)

Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)

[1] Logan, Robert. (2004 [1986]). The Alphabet Effect, p. 102.

[2] Hall, Stuart. (2012 [1980]). “Encoding/decoding,” p. 138.