The reversal of identity into credentials: the fallout of media targeting

A chapter from “The Digital Reversal” – #1 Amazon Hot New Release in Digital Media.

“The future of the book is the blurb,” said Marshall McLuhan. As the future arrives, this book is written in tweets – 1,295 of them. It’s a Tweetise – a reversal of the book. The digital shocks we are experiencing in politics, culture, and education are examined through the lens of reversal, as society is pushed to extremes by the digital speed of interactions. Check it out on Amazon.

Identity politics is a media effect. Over time, communication media have evolved from forms that largely ignored human differences to forms that now emphasize and spotlight them. The evolution of media has been worldwide and history-long identity training.

Writing depersonalized knowledge. Ideas gained value apart from the speaker, leading Aristotle to say: “Plato is dear to me, but dearer still is truth.” Choosing abstract “truth” over Plato—teacher and elder—would have been unthinkable in an oral-tribal culture.

Writing was “reader-blind,” focusing on ideas. Printing made literacy even more “user-agnostic.” As production grew, print materials had to compete. Accuracy in books and maps became a commodity, leading to editing and standardization, which represented ideals, not readers.

At first, the reading public eagerly read whatever printers offered. But as the market saturated, readers became more discerning. Different groups learned they had different interests. Printers had to tailor their production to more diverse and specific demands.

The characteristics of readers—their wants and social demographics—became relevant to content production. From that point on, printing could no longer ignore readers. Industrial production led to audience targeting. The journey toward identity politics began.

***

In the 19th century, the rotary press, pulp paper, and linotype made printing cheaper, bringing newspapers to the masses. Journalism broke free from the money and dictates of political sponsors. Instead, the press became dependent on the money and tastes of the masses.

Mass media became truly “mass.” Mass circulation led to the growth of advertising and profit. Profitability forced publishers and editors to be even more attentive to the desires and demographics of their audiences. News production shifted its focus from ideas to readers.

By drawing the masses into news consumption, mass media ignited the interest of the masses in public issues. It was no coincidence that the expansion of voting rights occurred at the same time, eventually leading to universal suffrage. Electoral populism emerged.

Mirroring industrial media production, the electoral populism of the industrial era quickly evolved toward more nuanced audience targeting. To win votes, politicians had to address different socio-demographic groups with their specific interests.

In the 20th century, readers’ and voters’ group identities became a significant factor in public life. Electronic media took audience targeting even further: measurement tools emerged that allowed identification of who the members of the audience were and what they liked.

In 1937, Paul Lazarsfeld and Frank Stanton of Columbia University designed the program analyzer, a device that registered listeners’ reactions to radio shows. The test group would listen to a program and press the left or right button when they liked or disliked what they heard.

Audience measurement allowed producers of news, shows, and ads to see which audience members, both individually and collectively, preferred which types of content. (By the way, this is how the “like” button was invented—70 years before social media.)

Similar methods were introduced for TV in the late 1940s. By the 1990s, an entire audience measurement infrastructure had emerged. Special remote controls tracked program choices by family members, allowing researchers to see what individuals from certain demographics preferred.

With this data, TV producers tailored content not just for kids, men, or women but for specific groups like “older working-class Black men” or “middle-class single white mothers.” This precise identification mirrors what is now called “intersectionality” in identity politics.

Media producers and marketers became obsessed with identity profiling to manipulate people’s behavior long before identity politics. It’s no coincidence that social philosophy developed identity concepts in the TV era. Foucault or Deleuze couldn’t have emerged in the print age.

Founded in 1980, CNN focused on news: editors sought to provide an objective picture. But 24/7 reporting quickly reached its limits, and the media reversed from facts to opinions. Fox News and MSNBC, launched in 1996, were audience-driven, catering to what their viewers wanted.

***

Digital media completed a centuries-long transition from focusing on content to focusing on users. Unlike past media, which targeted group identities, social media can customize newsfeeds and ads individually. To do this, they must know each user’s identity.

On social media, passive audiences of the literacy era reversed into participants expressing thoughts and emotions as in oral communication. Algorithms track their preferences through countless identity markers. The entire design is built to reward identity signaling.

Literacy is rational, orality is relational. Digital orality is mega-relational, because social media business critically depends on user engagement—on how actively people connect and react to each other. “The content became less important than the contact,” said Rushkoff.

Five billion users find themselves in a media environment that encourages self-expression, often in a fairly meaningless way—through likes or even by clicking links. This environment has conditioned people to believe that identity signaling matters.

Digital platforms urge: show yourself, identify who you are. Self-expression became as simple and effortless as a click. The labor of self-exposing clicks replaced the effort of doing; being became doing. This is how identity became more important than merit.

Digital platforms profit from users’ identity profiling, but users benefit too. By signaling their identity, users not only get a personalized newsfeed but also socialize within their preferred digital tribes with incredible ease—just by clicking.

Trained by media around the clock, people have internalized identity signaling as something worthy of reward—or punishment. Psychologists and life coaches now push us to find our “true selves” as a fix for problems that were once solved by effort—by actually doing something.

The more time people spend on, in, and with social media, the more identity signaling seeps into cognitive and cultural settings. For platforms, identifying users is a tactic to perfect targeting for profit. But this design, at scale, also affects social theories and practices.

Media are the hardware of society—the hardware has evolved from expressing ideas to centering on identities. The software—our culture—has followed suit. Identity politics mirrors the development of media, reflecting its cultural consequences.

Mass targeting in the press drove universal suffrage. TV’s audience targeting led to social theories of identity. Digital media completed the reversal of people’s identity into their worth. Social recognition flipped from what a person does to what a person is.

Along the way, digital media’s focus on identity signaling reversed the literate mind to a state typical of tribal societies based on oral tradition. Had Aristotle had Twitter, he would think that truth is fine, but dearer still is Plato.

However, there is a significant difference between oral tribalism and digital tribalism. In oral cultures, identity served as both a predictor and a prescriber. Defining or assigning a person an identity determined his or her tribal roles and tasks—identity prescribed behavior.

In contrast, in today’s social media environment, identity is behavior. Every action on social media is identity signaling that serves as a request for affirmation. Signaling identity is the digital labor that turns into the perks of socialization within respective digital tribes.

Because of social media, the need to signal identity has escalated and reversed identity into credentials. Online and offline, many people rush to declare their identities within socially favored categories as validation of their entitlement or moral virtue.

***

The new affordance for billions to submit their requests for affirmation is reshaping politics, culture, and ethics. By separating the known from the knower, literacy enabled objectivity and valorized truth. Mega-relational digital orality reverses truth into justice.

Because of its drive for uniformity, print literacy valued standards/normativity and kept minorities marginalized. With its focus on identity, digital orality has to reject normativity and marginalize the majority.

A new ethical premise has emerged: that someone “needs to be heard” (or “seen”). As it grew into an existential request, the need “to be heard” reversed from empathic recognition into a political demand.

Before, it was impossible to insist that someone “needs to be read” based solely on the fact of their existence. There was simply no such affordance. To enter the category of “must read,” a person had to first write something—and second, write something worthy.

Substance-based merits were embedded in social selection under the condition of literacy by default—due to its technical affordances. The considerable effort of writing and the high threshold of publishing filtered what society had on display.

The emancipation of authorship removed those limitations. Electronic, then digital media imposed a new imperative: representing “voices”—identities, not ideas. An idea is right if stated by the right person. The same idea may turn wrong if expressed by the wrong person.

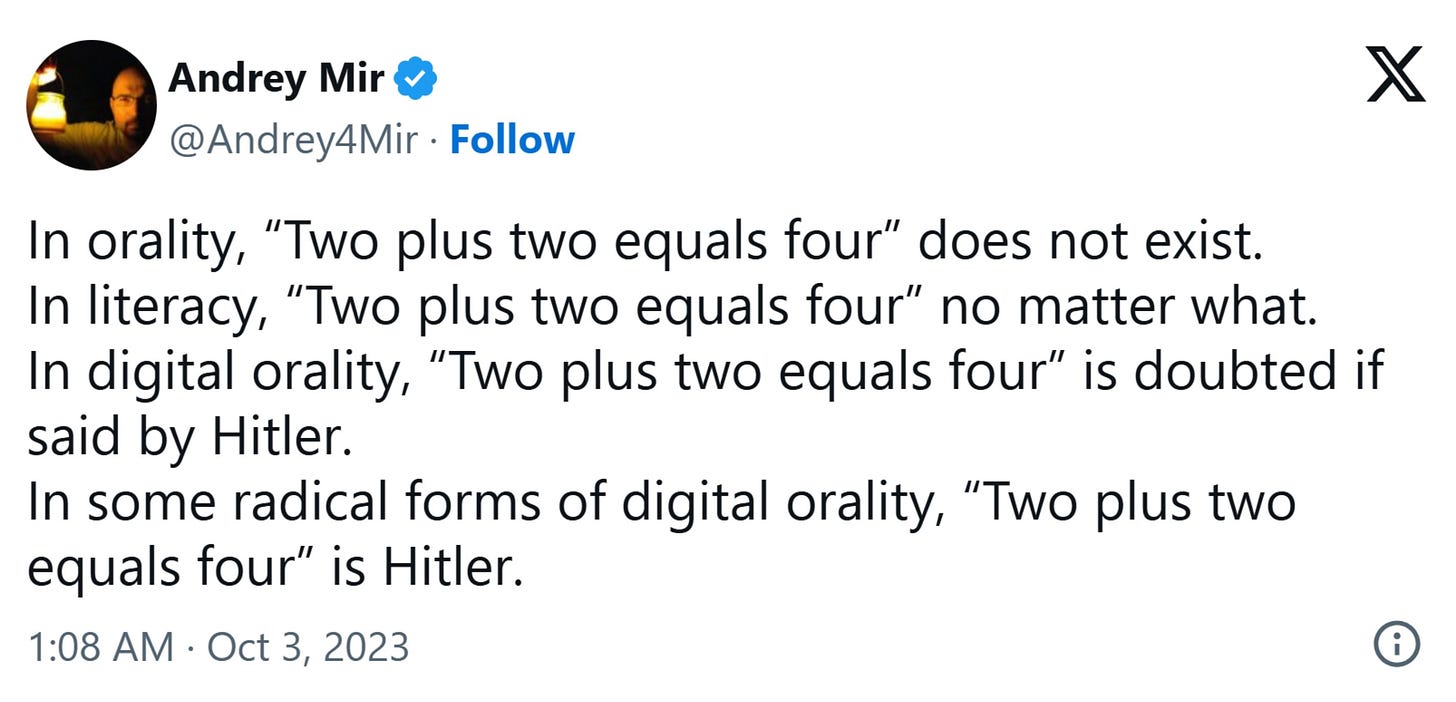

In orality, “Two plus two equals four” does not exist. In literacy, “Two plus two equals four” holds no matter what. In digital orality, “Two plus two equals four” is doubted if said by Hitler. In some radical forms of digital orality, “Two plus two equals four” is Hitler.

As media always sought customization, media evolution led society to see user identity—not deeds—as the primary determinant of social interaction. There’s no going back to a state when dominant media, like writing or early print, focused on ideas and ignored identities.

The media-driven focus on identity is here to stay; no one can reverse the reversal and return society to the supposedly healthier factory settings of literacy—because the focus on identity is the factory setting of the current media hardware of society.

Reed more: “The Digital Reversal” – #1 Amazon Hot New Release in Digital Media. Check it out on Amazon.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

🤯