William Kuhns: Mir-roring McLuhan in the digital era

Has anyone else writing today about the Internet and the new media it’s spawned, come off sounding as much like McLuhan on steroids?

A triple review of Andrey Mir’s:

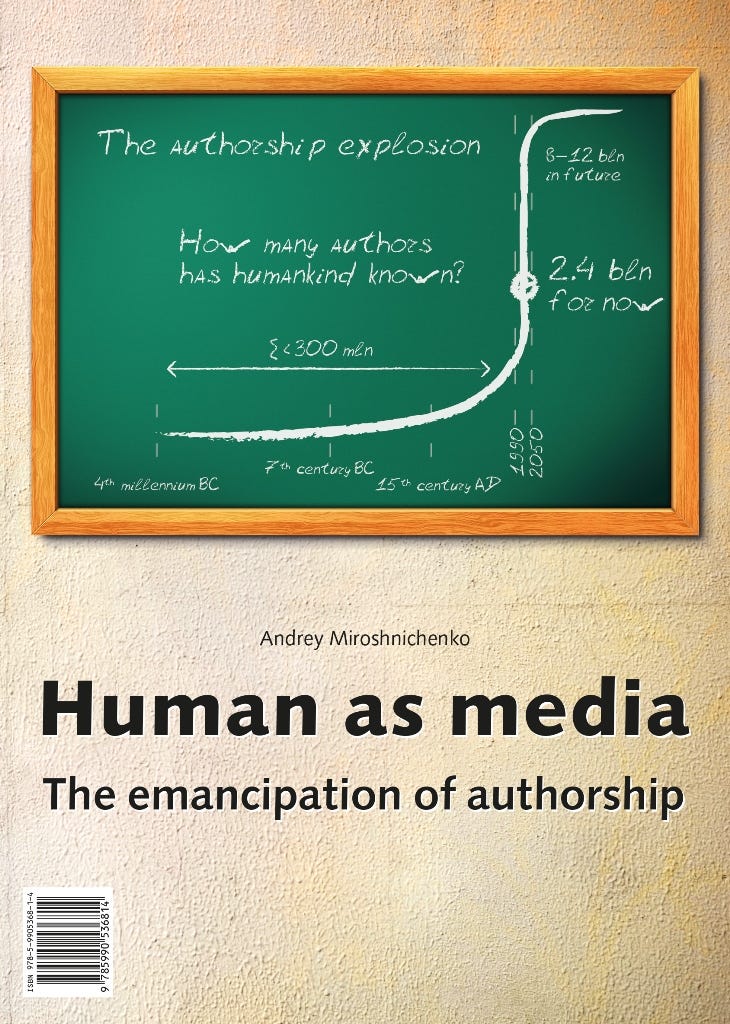

Human as Media: The Emancipation of Authorship (2014)

(Excerpts from William Kuhns’ review in: New Explorations: Studies in Culture and Communication, Vol 4 No 1 (Spring 2024).

<…> I have just finished reading all three of Mir’s books, and I’m struck, above all, at the sight in a 21st century mirror – should I say Mir-ror? – of McLuhan himself. The comparisons run strong and they often run deep.

Mir is a writer of startling, frequently breathtaking originality. His thinking and imagination roam very large territories. In three books, published within the last decade, Mir has shown himself to be a media theorist of audacious scope and fearless innovation. Often he cites and references McLuhan. More often, he does not have to. In his reach, in his incandescent insights, in his confidence that media are the progenitors of the fractures and potentials shaping our current history – I should add, of all history – Mir resolutely and resonantly echoes McLuhan.

Mir is our foremost epistemologist chronicling and probing the origins of today’s “truth decay.” He does this by widening and paving pathways originally forged by McLuhan.

The comparisons run deeper. McLuhan came into his own in his discoveries of media forms, “acoustic space” and the “global village” in the 1950s. What ignited McLuhan’s vast imagination – what created McLuhan – was the discovery of Harold Innis’s writings on media forms as the shapers of history and culture. The McLuhan who became supercharged by reading Innis’s media essays in early 1951 was months shy of turning 40.

Mir’s writings are those of man who emigrated to McLuhan’s city of Toronto in his forties and quit his career in journalism to become a media theorist.

McLuhan was a cultural outsider. He treasured his Canadian homeland and enjoyed his distance from America, citadel and engine of all the new technologies, from television to Xerography, that McLuhan so assiduously studied.

Mir(oshnichenko) was an outsider to the West most of his life. He grew up in Russia and worked there for the first two decades of his adult life. He saw the rise of the Internet and its effects both from afar, and at home.

Over a career that produced a dozen books, more than a thousand shorter writings, interviews and speeches, and upwards of 100,000 letters, McLuhan mapped the historic effects of media from language to print and more recently, the transformations we are all undergoing with our momentous and bumpy transition from literacy to the post-literate retribalization created by electronic and digital media.

Mir has, in three books – all written in the span of his first decade in Canada – provided the most cogent account to be found anywhere of how and why the shining promise to unite the world in our century – the Internet – has instead become its grand divider.

To say that Andrey Mir is the most vivid reflection of McLuhan to appear in our time feels like an understatement.

Here, in a passage from each of his three books in English, is Mir remarking on the sources of today’s polarization. As you read them, note how the image of McLuhan in this Mir-ror sharpens in each fresh iteration:

From Human as Media: The Emancipation of Authorship (2014):

The consequences of the new future are already being felt. The cultural gap between the online and offline leads to political tension within a country and between countries. There is a spectrum of resultant problems, from the introduction of censorship and the limitation of freedoms, to the growth in reactionism, extremism and terrorism.

From Postjournalism and the Death of Newspapers. The Media after Trump: Manufacturing Anger and Polarization (2020):

Compared to offline social practices, social media have powerfully facilitated socialization…The best mechanisms for gaining a response are simultaneously the most harmful for human relations.

From Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2023):

All the disruptions we identify as the consequences of political or cultural turmoil are, in fact, media effects. The near future will be defined by the struggle between literacy and orality. The struggle has been revived and intensified by digital media, which have taken the side of orality. Understanding the features of orality and literacy will help us to deal with the collateral damage we are going to suffer as a result of this media struggle.

Empowered by McLuhan’s insights, Mir has made it his mission to master the sources and processes that provoke, reinforce and expand our polarization. As well, he’s out to address that polarization, and perhaps forge some alchemic means that will enable us to overcome it. The upshot: Mir writes media theory with rare cogency and extreme urgency.

From the Introduction to Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror:

Why do people on social media become so polarized and deaf to logic and reason? Why do people read less and demand more? How do social media change minds and society? What comes next? The answer is digital orality. What is digital orality? This book starts a series of projects answering this question.

McLuhan had an oft-repeated recommendation for surviving the most tumultuous threats of technological change. He urged a reading of the Edgar Allan Poe story “A Descent into the Maelstrom” (1841). In that classic story, an aging sailor tells a younger man how his ship was once caught in the invincible clutch of a whirlpool. His brother, on the boat ahead of the sailor’s, succumbed to the maelstrom. So, soon, would the ship manned by the sailor telling this account. The sailor studied what happened when his brother’s boat went down. Everything stayed down except for a few empty barrels, which resurfaced. The sailor tied himself to a barrel and after undergoing a tempestuous plunge – his descent into the maelstrom – he and the barrel resurfaced. He was rescued soon after by the crew of a fishing vessel.

“Study the forces that would destroy you and learn how to master them,” McLuhan advised on innumerable occasions. “Escape into understanding.”

Andrey Mir impresses me as being the foremost investigator of today’s crushing forces of media and the most likely media theorist to discover a means to evade those forces. He is an astute observer of – and participant in – the most vital current element of the Internet, social media. He posts frequently on the medium previously known as Twitter, now known as X.

What has the Internet awakened?

One century ago, electricity served as the foundational energy source and driver of the century’s tools and innovations. It was also, if subliminally, the prime idea driving the poetry, the songs, the aspirations and thinking of the 20th century. The Internet is performing an identical role for the 21st. What does this mean, metaphorically and metaphysically? Conceptually, it certainly suggests that one central idea of our time is how collective behavior and thinking achieves a higher level of agency through fusion and emergence, or to use the scientific term for that emergence: stigmergy.

The Oxford Dictionary gives stigmergy this definition:

Simple behavioural rules change the environment in such a way that new rules are triggered by the new environmental stimuli.

Wiktionary gives stigmergy two definitions:

(biology) A mechanism of spontaneous, indirect coordination between agents or actions, where the trace left in the environment by an action stimulates the performance of a subsequent action.

(systems theory) A mechanism of indirect coordination between agents or actions, in which the aftereffects of one action guide a subsequent action.

Stigmergy needs a better brand name. As the quintessential driving idea of our time, stigmergy is a clumsy sounding word, not one we feel comfortable repeating, which is the first requirement of any effective name or brand.

Are there promising synonyms or alternatives?

Several ambitious recent books have focussed on emergence, beginning with Kevin Kelly’s 1995 encyclopedic Out of Control, which assembles an impressive range of models of non-hierarchical cooperation resulting in a higher level of agency. In 2001 Steven Johnson published Emergence: the Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities and Software, emphasizing how emergence serves as the primal driving vision of our era, dominated and driven by the Internet. Others followed, such as The Wisdom of Crowds by James Surowiecki (2004) and Here Comes Everybody by Clay Shirky (2008). Indirectly or directly, all these books address the phenomenon of Internet-gestated stigmergy. But none have come up with a succinct, fresh and appropriate name for it.<…>

What impressed me most on first reading Andrey Miroshnichenko’s uncommonly ambitious Human as Media (2014) is how he casually dubbed online stigmergy – that till-now nameless, emergent super-mind-like capacity of the Internet – giving it a fresh, accurate, and memorable name.

The Viral Editor.

The keystone of Human as Media is at the heart of Chapter 2, The Manifesto of the Viral Editor, which, in numbered points and subpoints, lays out the process by which early, distributed contributions to social media can aggregate and swell into coherent collective “thinking” which, in the best cases, will translate into sophisticated social action in the offline, or what we once called the “real” world. Mir introduces his stunning name and its stigmergic actions in this passage:

It would seem that unrestricted access to publishing means the triumph of anarchy. And on an informational level, the triumph of cacophony and noise. For none of this happens without noise.

At the same time, the environment of free authorship nevertheless has a built-in mechanism for determining value, compensating for the imbalance of authority and point of reference. I call this mechanism the Viral Editor…

The Viral Editor is a distributed being of the Internet, a sort of Artificial Intelligence whose “processing chips” are the people – users…

Identifying something of interest, a random user passes this information through his or her personal interests filter, conducts his or her own microediting and publishes his or her message, and he or she does so without any restrictions…

This is the same work that a professional editor is doing.

Here I must apologize. In my eagerness to spotlight “Viral Editor” in the context of its adjacent literature, I see that I have dashed past the starting points of this vibrant and awakening book.

Human as Media: The Emancipation of Authorship (2014) originally struck me as an odd title. I was reminded of McLuhan’s “Nothing is so human about us as our technologies.” (1975 8) On giving it more thought, I saw how Mir posits that when knowledge and meaning are liberated by new media, humanity is awakened because peoples’ spirits are liberated. “The history of humankind [can be read] as a fight for freedom of content,” he writes (2014, 6), and we must recognize that for Mir, “content” is synonymous with “meaning”.

Human as Media celebrates the new media – the Internet and particularly social media – with a strong accent on their requirement that we participate, and that, to participate, we all must contribute, we must all become authors and publishers. “I publish, therefore I am.” The Internet, Mir tells us, is the third of three great emancipators.

The first emancipator, which first appeared in the 8th century B.C.E. with Egypt’s demotic script, was Writing:

As a result, the palaces and temples lost their monopoly over the production of information. This process took several hundred years, leading to the downfall of Ancient Kingdoms. In its aftermath, new civilisations appeared, each armed with a phonetic script: Greece captured minds, while Rome captured lands.

Just over two millennia later – in 1445 to be exact – came the Gutenberg Press, and with it, the Emancipation of Reading. What followed was the collapse of those later regimes which also maintained their power by their fiercely guarded control of information:

Then came the Reformation, religious wars and political revolutions. Palaces and temples once again lost their monopoly, this time over the interpretation of content. As a result of Gutenberg’s invention, monarchs were beheaded, world maps were redrawn, vaccinations were developed and man went into space. Modern society and modern economics were born.

The third emancipation, the Emancipation of Authorship, appeared only very recently, with the universal spread of the Internet and the emergence of social media.

Personal computers as well as mobile devices with Internet connectivity have given all individuals the unlimited right to share their thoughts with others, whatever their reason, or even if they have no reason. This does not mean that every private message is worthy of attention. It means that the palaces and places of worship have again lost their monopoly, this time over the production of meaning.

That passage, on first reading, gave me a nostalgic goosebumps. Has anyone else writing today about the Internet and the new media it’s spawned, come off sounding as much like McLuhan on steroids?

Mir has a further premise in Human as Media: to engage with the Internet is, implicitly and implacably, to take on the responsibility of authorship. Not so much of single-authored books as we’ve known them since the Gutenberg revolution, but of collaborative works constructed by the Internet’s many contributors, and fine-tuned by the Viral Editor. Mir writes:

I publish, therefore I am. Publishing is turning from an opportunity into an obligation. And the further we go, the truer this becomes. This is only logical, because publishing has become a means of socialisation. (2014 9)

In the concluding section of Human as Media, Chapter 3, The Social Impact of the Net, Mir(oshnichenko) showcases accomplishments of the Viral Editor. <…>

In Human as Media, Mir demonstrates another way of Mir-roring McLuhan. Although English is his second language, Mir writes English with such facility that, very often, his remarks take on the snap and felicity of McLuhan’s quips and zingers. From Human as Media, a sampling of its sparkling lines:

“Contemporary barbarism does not predate civilization but accompanies it. Extremism is motivated not by poverty, but by a feeling of injury and loss.”

“With every release of content, society sheds its old form, like a snake sheds its skin.”

“The minimum level of engagement in the Internet is equal to the maximum level of engagement with the old media.”

“Emancipation of authorship has this incidental effect: the audience itself becomes the author.”

Human as Media voices high hopes. Many of those hopes were soon to be dashed: in Russia, by the crackdowns of Vladimir Putin; in social media throughout the West, by the succubus of greed that tweaked algorithms so they torqued content into becoming dopamine-addicting brain candy and, by seeking out and accenting high-pitched emotional involvement, pounded into us the early wedge of what would crack open into an acute and expanding polarization.

By 2014, when Human as Media was published – in keeping with Mir’s notions of liberated authorship, self-published – Andrey Miroshnichenko had moved his family to Toronto, shortened his name to Mir, and set to work on the book that would be his goodbye salvo to his decades spent in Moscow as a professional journalist.

He forged that goodbye in thunder.

Of all the McLuhan-inspired studies I have read, I cannot recall one as passionate or emotionally charged as Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020).

Mir’s swan song to classic journalism is etched as much in sorrow as in anger.

In large part, the story Mir tells is a tale of economic desperation. For over a century, newspapers in America and elsewhere had profited, and occasionally prospered, by publishing advertising alongside the news stories. The ad-sponsored newspaper reached an audience that was educated, rational, and, for the most part, politically moderate. A world based on such readers had a political spectrum like a bell curve: bulging in the middle and slackening off on both ends.

Then came the Internet, which nibbled away at newspapers like sharks feasting on a stranded, infirm whale.

The most savage bites were economic. In 2000, newspaper ad revenue in America came to $19.6 billion. But the foundation was shifting. The Internet offered advertisers the unprecedented advantage of high-precision targeting. In 2013, Google alone attracted ad revenue of $51 billion. By 2018, newspaper advertising had dwindled to $2.2 billion.

Newspaper publishers sought to remedy the shortfall by selling digital subscriptions. This model had an unexpected downside. Bad news has always been top selling news. To attract readers, publishers and editors stressed stories that provoked anger and fear, what George Will describes in a Washington Post column about Mir’s book as “fertilizers of polarization.” (Will, 2022)

Another source of the newspapers’ demise came from the newspapers’ efforts to compete with the newsfeed of social media. The newspaper story had long been a well-wrought piece of writing, with story mattering more than headline. Classical news stories were written narratives that favored what Mir calls “’long range’ rationality.” He points out that post-print media, such as radio, TV, and now the Internet, favor what he calls “short-sighted emotionality.”

To compete with short-sighted media, newspapers went online and ceased to follow the firm practice of an-edition-once-every-24-hours. Journalism became “churnalism”, a race to publish more with less, producing a feverishly assembled hodgepodge of headlines, teasers and clickbait. Journalists trained and experienced in the craft of investigating and writing complete stories were forced to keep up with an hourly feed requirement, a flailing scenario of spin-the-wheel-and-spit-out-a-news-nugget: in Dean Starkman’s caustic label, “the hamsterization of news.”

Headlines would supposedly lead readers to longer stories and, hopefully, subscriptions. But seldom do the readers of churnalism seek out the larger narrative. “News bits turn into new baits,” Mir writes, “that do not lure a reader but rather feed him into satiety.”

The subjugation of larger stories to this process – the medium masticating, mincing and minimizing its message – has led to many consequences, including the primacy of the short and emotionally provocative over the lengthy, narratively developed and thought-out. This is postjournalism, news adapted for the post-literate skimmer, not the classic literate reader of news. In Mir’s telling, postjournalism is one of the foremost contributors to a fracturing of society and its subsequent polarization.

Mir’s Postjournalism can be read as a study in unexpected consequences. No one foresaw the “Trump bump” or warned news sources about it. In 2016, a man who craved attention at a psychotically emboldened narcissistic fever pitch became the showpiece of every news broadcast in America, and was granted so much airtime – CNN’s start-to-finish coverage of his rallies were often kept commercial free – that in November, Trump surprised all the pollsters, and himself, by winning the American presidency. No one foresaw the Internet, once regarded as the harbinger of world democracy and the seed of Teilhard de Chardin’s Noosphere, a world-enfolding global mind, becoming instead the paradigmatic dynamic driving polarization, resentment, and the potential demise of democracy in America. No one foresaw journalism morphing from a journalist-driven source of trusted information to an audience-prompted source of validation.

Mir’s conclusions are unsettling but self-evident. Red and blue citizens alike, we no longer turn on or read news to learn what’s happening; we look to the news to validate our tribal identity. News has ceased to serve an appetite for information: we, of whichever tribe, turn to news for affirmation. This has flipped the news production process inside-out. Whether the news channel is CNN or BBC or Fox News, the effect is the same: the news of the day has been shaped into the day of news, tilted and phrased to be most palatable to its audience. Increasingly, as a result, the world described out there is being reshaped to resemble the world as adherents of the targeted tribe wish it to be. The New York Times, as Martin Gurri remarks, has gone from being the paper of record to a hymnal for the liberal faithful. (Gurri 2021) In a postjournalism world, the neotribalizing process McLuhan forecasted has, clearly, infected not only post-literates but the literate as well.

As we’ve come to expect from Mir, Postjournalism is flecked with more of his well phrased aphorisms.

[The post-internet models of funding newspapers] are similar in their impact on journalism. They require newsrooms to operate with values, not news. This slowly forces journalism to mutate into crowdfunded propaganda – postjournalism.

[T]he conflict between social media and the mainstream media is always the conflict between the underrepresented and the establishment.

The news bits (teasers, recaps, headlines, etc.) act as particles when representing pieces of the world picture mosaic. However, when reassembled in a personal newsfeed, they act as the flow, with resonating waves that enable the viral behavior of news on social media… it is a “particle-flow duality” which is the most natural way for news to exist.

Print, with its delayed reactions to linear thought, started the Age of Reason; social media with their instant service of accelerated self-actualization, has turned the Age of Reason into the Age of Rage.

If Postjournalism often reads like the somber words of a coroner, standing over an autopsy table, describing the lesions and contusions that turned a living man into a comatose, occasionally twitching, soon-to-be-corpse, Mir’s followup book, three years later, goes in search of the larger forces that have driven this disaster to happen in the first place.

In Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Robert Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2023) – a book sure to become a cornerstone of media ecology literature – Mir expands his ambitions and zooms out to examine the anomaly in which history itself backtracks on its own most enlightening transitions. At epic length, in a narrative that has been assembled with phenomenal detail, Mir examines how “the contours of the digital future resemble patterns from the tribal past.”

“Throughout history man has become the being that strives to rise above itself.” wrote the Swiss-German philosopher-historian, Karl Jaspers (1883-1969). In his 1948 book The Origin and Goal of History, Jaspers inquired into the source of that striving. He proposed that between 800 and 300 B.C.E., humanity invented the core elements of the civilizations that would follow. Over those 500 years, primarily in Greece, China, and India, the fonts of future civilizations, and eventually, a world civilization – and what in the postwar 20th century would coalesce into a world civilization – humans awakened to their fully rational nature and their imaginative, technical, artistic and spiritual potentials. Jaspers named that arc of awakening the Axial Age.

Because of the Axial Age’s many breakthroughs, Jaspers writes,

[Man became] capable of contrasting himself inwardly with the entire universe. Man discovered within himself the origin from which to raise himself above his own self and the world.

Something vital is missing in Jaspers’ assessment. What sparked the Axial Age? What vital ingredient, added to man’s brewing capabilities, proven in hunting, in agriculture, in the early arts and in Bronze Age technics, ignited those talents into that extraordinary potential achieved in the Axial Age?

Here Mir turns to a McLuhan collaborator from the 1970s, Robert Logan, a now-retired physics professor from the University of Toronto (and editor of this very journal). Logan’s far-reaching 1986 book The Alphabet Effect: the Impact of the Phonetic Alphabet on the Making of Western Civilization provides the missing spark.

In his account of the Axial Age, Jaspers makes little of writing; it is but a minor figure in his grand tapestry.

But by giving a thorough examination of the rise of written expression from early notations like knotted cords, pictograms and hieroglyphics, to the fully formed alphabet – and examining early and slower effects of writing, often through the observations of the author of Preface to Plato, Eric Havelock – Mir expands Jaspers’ canvas to newly epic dimensions.

Jaspers’ Axial Age becomes, in Mir’s hands, the Alphabet-Roused Axial Age.

“[A]ll the key features of the Axial Age, as described by Jaspers, align with the effects of the transition from orality to literacy,” Mir writes.

With his typical audacity and breadth of imagination, Mir has taken up Jaspers’ bold claim and held it to another Mir-ror: here is what the world is about to depart from because of its commitment to a digital future, Mir says, planting his flag on what is arguably the most original fresh ground that McLuhan discovered: history-as-palindrome.

McLuhan put it this way in The Gutenberg Galaxy:

Western man knows that his values and modalities are the product of literacy. Yet the very means of extending those values, technologically, seems to deny and reverse them.”

A decade later McLuhan put it another way:

Paradoxically, electronic man shares much of the outlook of preliterate man, because he lives in a world of simultaneous information, which is to say, a world of resonance in which all data influence other data. Electronic and simultaneous man has recovered the primordial attitudes of the preliterate world.

McLuhan never used the term “digital orality,” the engine driving Mir’s Digital Future. “Digital orality” was a phrase invented by Robert Logan. (2007)

Perhaps the most frequently uttered of McLuhan’s pet phrases – used anytime, anywhere – was “acoustic space,” which McLuhan preferred over “orality”, because “acoustic space” evoked the world as it was known to all those who came before literacy. Walter Ong, who did the first major followup on the transition from orality to visually grounded literacy, used “primary orality” and “secondary orality” to distinguish between pre-writing and post-electronic forms of orality. Mir frequently and gratefully nods to Ong but chooses Logan’s phrase “digital orality” as the foundation element of the world that we all move into as our lives and our institutions go fully digital.

Mir’s own primary concern issue is to address society’s rapidly growing polarization. On November 9, 2020, Mir tweeted, “Polarization studies are media studies.”

McLuhan spoke often of the postliterate condition into which the world was moving. But McLuhan never gave post-literate orality the organized and detailed attention it receives in Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror.

In its organization and rich assembly of detail, Mir’s Digital Future resembles the massively researched and intricately woven approach taken by McLuhan’s most astute and committed disciple, Walter Ong – who gave orality its most profound and resonant soundings with The Presence of the Word (1967) and later, Orality and Literacy (1982).

With Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror, Mir is not only filling in the blanks suggested in McLuhan’s sweeping pronouncements about a postliterate society, Mir is conquering fresh ground, mapping the contours of an uncharted, highly polarized world. McLuhan’s suggestion that “we experience, in reverse, what pre-literate man faced with the advent of writing” (1955 2) serves as Mir’s runway. The map and its broadest coordinates are thoroughly McLuhan’s. Mir’s Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror, is audaciously and imaginatively a total original.

Exactly what is orality? Helen Keller (1880-1968), robbed of both sight and hearing by a freak childhood illness, was once asked which she regarded as the greater liabiliity: her blindess or her deafness. She was thirty when she penned this reply:

Deafness is a much worse misfortune. For it means the loss of the most vital stimulus – the sound of the voice that brings language, sets thoughts astir and keeps us in the intellectual company of man. (Keller 1910)

A shortened version has become a widely quoted meme attributed to Keller, though she probably never used this exact phrasing: “Blindness cuts us off from things, but deafness cuts us off from people.”

Here, in a nutshell, is the power of the oral, that it binds us to one another and makes those human bonds the root source of all our interactions with the world. The oral gives human connections, and the perceptions and feelings and cognitions rooted in those connections, primacy over any other form of perception and cognition. For anyone searching the full power of the oral, I heartily recommend both Walter Ong’s The Presence of the Word: Some Prolegomena for Cultural and Religious History (1967) and Andrey Mir’s Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect. <…>

Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror can be read as a comprehensive inventory of the transformations triggered by the shift from an oral to a literate mindset, and subsequently, in our day, the reverse. Most of these transformations appear in McLuhan, but not in such a superbly researched and crisply organized presentation as Mir provides.

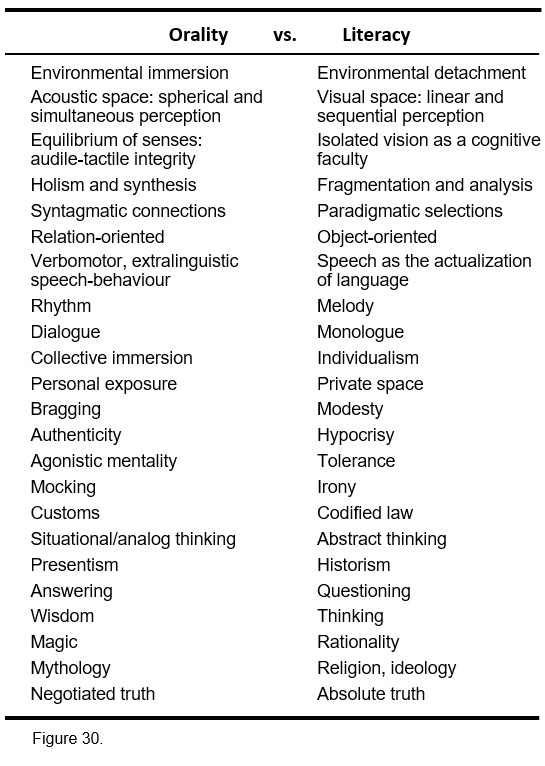

At the very end of the book’s text, Mir, as our premier epistemologist, presents a chart of the major thematic shifts he has tracked. His chart “Orality vs Literacy” lists the transformations of 20 modes of knowing and relating to the world as they are transmogrified from an oral mindset to a literate mindset. The chart is a map richly reminiscent of the “Print to Electronic Media” chart by Lewis Lapham in his scintillating Introduction, “The Eternal Now,” to the 1994 MIT Press reprint of McLuhan’s Understanding Media. I cannot offer a better precis of the threads explored in Digital Future than by reproducing Mir’s wonderful map. If you cannot read the book, I urge you to master this map. Our future is written in its left hand column. Our present and upcoming stresses and fractures are spotlighted in the divisions between the two versions of ourselves presented here.

Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror is such a sweeping narrative I hesitate to try encapsulating it all in a single description. Instead, I will dip into a few portions and present samplers.

Chapter 1, “Media Ecology of Changes,” reminds us of Mir the highly qualified journalist. He lays out environmental effects of the escaped hippos of Pablo Escobar, the reintroduced wolves of Yellowstone Park, the poisoned vultures in the skies over India, and the exterminated sparrows of China, to illustrate the complex and interwoven nature of an ecology. Media ecology is premised on the notion that new media reshape our human world in ways deeply analogous to the addition or removal of a linchpin species in a natural ecology.

Chapter 7, “A catalogue of the effects of writing and the alphabet”, should be published as an Addendum to any future editions of Karl Jaspers’ 1948 Axial Age thesis, The Origin and Goal of History. Chapter 7 presents in sharp detail how the alphabet separated the knower from the known and thus awakened abstract thinking. With substantial reliance on Robert Logan’s groundbreaking catalogue of the effects of the alphabet in The Alphabet Effect (2016 [1986]), Mir tracks how the alphabet became the inventor of Nature, Individualism, classification, and codified law.

In Chapter 11, “The meaning and goal of history when the medium is the message”, Mir presents literacy as a spectrum, probing such distinctive modes as semi-literacy, residual literacy, craft literacy, and phantom literacy.

In his Conclusion, “What was the Axial Age anyway?” Mir proposes that the Axial Age was ultimately a “parenthesis” between original tribal and neo tribal cultures. If this is the case, what comes next? Mir cites the forecaster and inventor Raymond Kurzweil who claims that as Artificial intelligence advances to become one million times more intelligent than the human mind, history will reach a point called the “Singularity”, which Kurzweil defines as “a profound and disruptive transformation in human capability.” (Kurzweil 2005 136)

What does Mir make of all this? “The Digital Axis may end up in the awakening of the next, non-biological iteration of intelligence in the place of humankind.” (2023a 308) In short, the media that, in the Axial Age, gave birth to all that makes us fully human and civilized, may also, in the much speedier “Reverse” Axial Age, give birth to what puts an end to us.

Digital Future in the Rear View Mirror is replete with adroit and insightful passages:

The cognition of the world in orality produces wisdom. The cognition of the world in literacy produces thinking. Wisdom has answers; it is a storage of precedents. Thinking has questions; it is an endless process of inquiry.

Orality values subjective relations over objective truth, whereas literacy values objective truth over subjective relations… Digital orality reverses the latter and retrieves the former.

For a digital being, the sense of an empty or full stomach will be replaced by the sense of an empty or full bank account or rather a social score account. The sense of fullness-emptiness mimics physical properties but, in the digital, is social and time-biased.

This new [digital] environment is space-ignorant and time-biased, representing the tectonic shift of the sensorium towards time. The colonization of digital space is essentially the utilization of time.

Since media are extensions of humans, media evolution exploded humankind into the world. The final stage of this explosion, the Singularity, will also be the last reversal – it will implode the world into humankind, when humankind, its new medium, and its environment become one.”

By Way of a Conclusion

In his three books, Mir has announced that if we wish to understand what Roberto Calasso has called our “unnameable present,” we need to understand digital orality and the most decisive fracture points where the new orality breaks from literacy, as in the transition from objective truth to interpersonally mediated – negotiated – truth.

Mir has done us a great service in articulating brilliantly the sources of our polarization.

Yet has he suggested how we can grow beyond it, heal it, learn from it? Are there ways in which both sides of the divide could collaborate in finding middle ground – ways that do not involve one side “winning,” the other side “losing”? Can we find common ground through, and not despite, our advances in digital media of communication?

I recommend a snappy 2022 essay Andrey Mir published in the online City Journal: “A Modest Proposal to Elon Musk.” In it, Mir acknowledges that the two most promising avenues for overcoming the media-widening divide are media literacy and changes in the engineering design of the media. His proposal to Musk, who was at the time in the process of purchasing Twitter for $44 billion, came down to a pitch for changing the design of the medium of sending tweets. Here’s the nut of Mir’s proposal:

In 2020, Twitter tested prompts that encouraged users to pause and reconsider a potentially harmful or offensive reply before they hit “send.” When given such a prompt, 34 percent revised their initial reply or decided not to send their reply at all. Twitter also began prompting users to read an article before retweeting it. But these all were drops in the bucket. For a radical change in settings affecting billions of interactions, a solution is needed that will strike at the core.

So here is the promised piece of advice to Musk: require a character minimum for tweets. The fundamental feature of Twitter is its limit of 280 characters for a post. Brevity was considered a virtue for a writer in the print era, but on Twitter, brevity has nothing to do with a sender’s virtue. Quite the opposite: short tweets tend to be short on rationality. In this medium, brevity is a business gimmick that makes the news feed faster and easier to engage with. What is needed to reverse radically this feature of social media is an opposite limit: tweets must not be shorter than 280 characters. A quantum of media must become time-consuming again, inhibiting responses via a technical delay into which thoughts, not emotions, might be squeezed. Alternatively, Twitter could prioritize longer posts, or give perks to users authoring thoughtful content.

This would encourage an unthinkable outcome for social media: requiring a user to think about what to write. And that renders it extraordinarily unlikely. After initial hype, such rules would undermine engagement, which lies at the core of Twitter’s business model. It could accelerate the takeover of non-textual media, such as TikTok. But solutions that slow down social media engagement cannot be driven by market imperatives. A source for such solutions, though, might be the arbitrary will of an eccentric owner—one who does not care much about the platform as a business and whose ambitions are peculiar enough to include sending humans to Mars.

Excerpts from: Kuhns, William (2024). “Mir-roring McLuhan in the digital era: How Andrey Mir adapts and addresses Marshall McLuhan’s thought to the age of MAGA and divisive media.” New Explorations: Studies in Culture and Communication, Vol 4 No 1 (Spring 2024).

See also books by Andrey Mir:

Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)